Tijl Uilenspiegel is a fictional character from Dutch-German folklore, who became legendary in Flanders as the hero in Charles de Coster's novel of the same name. Legend has it that Ulenspiegel was a rascal who traveled freely as a bird through the Netherlands and Germany (known there as Till Eulenspiegel) in the sixteenth century, fooling everyone with his tricks.

In De Coster's novel, Ulenspiegel is assisted by his good-natured fat friend Lamme Goedzak and his girlfriend Nele. In De Coster's stories, Tijl has, in addition to his roguish reputation, the status of resistance hero against the Spanish occupation of the Netherlands in the 16th century. With this, the figure in Flanders now has the reputation of "spirit of Flanders". Ulenspiegel would once have been in Lierderholthuis, a village that now falls within the municipality of Raalte. Here on a square is a sculpture by Tijl Uilenspiegel, made by artist Frank Stoopman. Also in Damme, the city where he was born according to the book by Charles de Coster, is a statue representing Tijl.

History:

Although Charles de Coster left behind the most famous version of the Uilenspiegel character in the Dutch language area, Tijl is not the fruit of his imagination.

The first stories about Tijl Uilenspiegel appeared in Germany around 1500. Herman Bote, town clerk of Brunswick, wrote some funny anecdotes about a character called "Dil Ulenspeghel". This medieval Ulenspiegel differs in many ways from the later nineteenth-century novel: the political and social-critical dimension is missing and the humor is much more vulgar, to the point of vulgar. His name explains his talent to fool people. At that time the owl was still a symbol of stupidity (which is why in paintings by Hieronymus Bosch an owl can often be seen with stupid characters, compare the word 'owl chick' and the Flemish expression 'it's quite an owl.' (' t's quite a fool)). The mirror functions as a thing in which people see themselves as they are: "as stupid as an owl". De schalkse Tijl shows people as they are, without any hesitation. Hence his name, which he himself explains in the first pages of the book: "I am your mirror," Ulen-mirror.

The book formed the basis for many 16th century folk tales about the same character.

In the Netherlands, the first book about Tijl Uilenspiegel was printed in Antwerp between 1525 and 1547 by Michiel van Hoochstraten. The full title was: "Ulensoepelhel, Van Ulensiegelhel's life ende schimpelijcke wercken, and the wondrous adventures he had, because he and did not let him down."

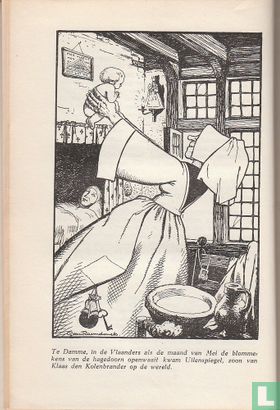

The most famous version of the story, however, is that of the (French-speaking) Belgian author Charles de Coster: "La Légende et les Aventures héroïques, joyeuses et glorieuses d'Ulenspiegel et de Lamme Goedzak au pays de Flandres et ailleurs" (1867). De Coster gives birth to Tijl in Damme in West Flanders (the first sentence of the book reads: "When the month of May opened up the flowers of the hawthorn, Uilenspiegel, Klaas's son, was born in Damme"). Tijl was born in 1527, on the same day as Philip II.

De Coster's Tijl Uilenspiegel is more than a light-hearted vagabond and mischievous boy: he is a Flemish freedom fighter who fights against Spanish rule on the side of the Geuzen. Since then, Uilenspiegel has been associated with Flanders, although the original medieval Uilenspiegel did not have this patriotic dimension. The first Dutch translation of De Coster's adaptation appeared in 1896.

Charles de Coster and the Flemish movement:

Charles de Coster was born in Munich in 1827 as the child of a Walloon father and a Flemish mother. Although he was French-speaking, he had a great sympathy for the culture and vernacular of Flanders. The idea for his novel arose during his studies at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), where his friend Félicien Rops had founded a satirist magazine in 1856: "Uylenspiegel. Journal des débats littéraires et politiques".

De Tijl Uilenspiegel by Charles de Coster is, as we saw earlier, a freedom fighter: a Flemish Ivanhoe or Willem Tell, who fights alongside the Geuzen against Spanish rule. The entertaining dialogues between the two characters are unmistakably reminiscent of that other immortal master-and-servant duo: Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.

The Flemish Movement, flourishing in those years, which worked hard for the revival of Flemish culture, closed this militant, flamingante Tijl in its heart. Thus, contradictory enough, the De Costers novel became a French-language tribute to Flanders ...

The liberalism of Tijl Uilenspiegel:

De Tijl by Charles De Coster has a liberal, free-spirited vision of life, just like his creator, with an urge for truth and honesty. And just like the writer himself, Tijl became a socially engaged figure, possessed by a drive for self-determination in a broad humanist setting.

An incorrigible gruel eater:

The anti-clerical elements are already discussed at the beginning of the book when the newborn Tijl is baptized no less than five times in one day.

Yet Tijl in itself is not a religion hater. He does, however, strongly criticize the wars of religion (the book is set during the heyday of the Counter-Reformation) and the persecution of heretic that ravages the country. His father is burned at the stake, suspected of Lutheran sympathies, the nurse Kathelijne loses her mind after the terrible torture she, accused of witchcraft, has to endure. Ulenspiegel observes and denounces the injustice and abuses of the Inquisition: a freebooter who, literally, knows neither god nor commandment: thus he hires himself from the pastor and steals his horse, and sells horse manure to Jews, making them believe that it is prophetic. grains with which they can predict the return of the messiah. Punished and sentenced to make a pilgrimage to Rome, Tijl also fools the Pope himself!

"Tijl Uilenspiegel" later revised and edited:

Charles de Coster's book has been edited by many other authors:

one of the best-known adaptations is the theater version that Hugo Claus made of the Uilenspiegel legend in 1965.

Willy Vandersteen made two comic albums around Tijl Uilenspiegel, but added a touch of his own fantasy. The comic series Suske en Wiske also refers to Ulenspiegel a few times. In The Steel Flowerpot (1950), Lambik and Wiske walk along the harbor of Amoras, when Lambik begins to praise the great achievements of Flemish people in the past, including Tijl Uilenspiegel. However, Wiske remarks: "As long as you don't forget that Lamme Goedzak was Tijl Uilenspiegel's buddy, you can continue talking, Lambik." In The Krimson Crisis (1988), Tijl Uilenspiegel is flashed to the present.

Richard Strauss wrote the symphonic poem (Till Eulensdichtels lustige Streiche), inspired by the legend.

In 1961 there was an eponymous youth series about Tijl Uilenspiegel.

pages: 580 pages, with two black and white illustrations

This text has been translated automatically from Dutch

Click here for the original text

Tijl Uilenspiegel is een fictief figuur uit Nederlands-Duitse folklore, die in Vlaanderen legendarisch werd als de held in Charles de Costers gelijknamige roman. Volgens de legende was Uilenspiegel een deugniet die vrij als een vogel in de zestiende eeuw door de Nederlanden en Duitsland (daar bekend als Till Eulenspiegel) trok en iedereen voor de gek hield met zijn streken.

In De Costers roman wordt Uilenspiegel bijgestaan door zijn goedmoedige dikke vriend Lamme Goedzak en zijn vriendin Nele. In De Costers verhalen heeft Tijl behalve zijn schelmenreputatie ook de status van verzetsheld tegen de Spaanse bezetting van de Nederlanden in de 16de eeuw. Hiermee kent de figuur in Vlaanderen nu de reputatie van "geest van Vlaanderen". Uilenspiegel zou eens in Lierderholthuis zijn geweest, een dorpje dat nu binnen de gemeente Raalte valt. Hier op een pleintje staat een sculptuur van Tijl Uilenspiegel, gemaakt door kunstenaar Frank Stoopman. Ook in Damme, de stad waar hij volgens het boek van Charles de Coster geboren werd, staat een standbeeld dat Tijl voorstelt.

Geschiedenis:

Hoewel Charles de Coster de in het Nederlandse taalgebied bekendste versie van het Uilenspiegel-personage heeft nagelaten, is Tijl toch geen vrucht van zijn verbeelding.

De eerste verhalen over Tijl Uilenspiegel verschenen rond 1500 in Duitsland. Herman Bote, stadsklerk van Brunswijk, schreef een aantal grappige anekdotes over een personage genaamd "Dil Ulenspeghel". Deze middeleeuwse Uilenspiegel verschilt op veel punten van de latere negentiende-eeuwse roman: de politieke en maatschappijkritische dimensie ontbreekt en de humor is veel platvloerser, op het vulgaire af. Zijn naam verklaart zijn talent mensen voor de gek te houden. De uil was toen nog een symbool van domheid (vandaar dat er op schilderijen van Jheronimus Bosch bij domme personages vaak een uil te zien is, vergelijk ook het woord 'uilskuiken' en de Vlaamse uitdrukking "'t is nogal een uil." ('t is nogal een domkop)). De spiegel fungeert als ding waarin mensen zich zien zoals ze zijn: "zo dom als een uil". De schalkse Tijl laat de mensen zien zoals ze zijn, zonder enige schroom. Vandaar zijn naam, die hij zelf in de eerste pagina's van het boek verklaart: "Ik ben ulieden spiegel," Ulen-spiegel.

Het boek vormde de basis voor vele volksverhalen uit de zestiende eeuw over hetzelfde personage.

In de Nederlanden werd tussen 1525 en 1547 in Antwerpen door Michiel van Hoochstraten het eerste boek over Tijl Uilenspiegel gedrukt . De volledige titel luidde: "Ulenspieghel, Van Ulenspieghels leven ende schimpelijcke wercken, en de wonderlijcke avontueren die hij hadde want hij en liet hem geen boeverie verdrieten".

De bekendste versie van het verhaal echter is die van de (Franstalige) Belgische auteur Charles de Coster: "La Légende et les Aventures héroïques, joyeuses et glorieuses d'Ulenspiegel et de Lamme Goedzak au pays de Flandres et ailleurs" (1867). De Coster laat Tijl geboren worden in het West-Vlaamse Damme (de eerste zin van het boek luidt: "Toen de meimaand de bloemen van de meidoorn deed ontluiken, werd Uilenspiegel, de zoon van Klaas, in Damme geboren"). Tijl ziet het levenslicht in 1527, op dezelfde dag als Filips II.

De Tijl Uilenspiegel van De Coster is meer dan een luchthartige vagebond en kwajongen: hij is een Vlaamse vrijheidsstrijder die aan de zijde van de Geuzen tegen de Spaanse overheersing vecht. Sindsdien wordt Uilenspiegel met Vlaanderen geassocieerd, hoewel de oorspronkelijke, middeleeuwse Uilenspiegel deze patriottische dimensie niet bezat. De eerste Nederlandse vertaling van De Costers bewerking verscheen in 1896.

Charles de Coster en de Vlaamse beweging:

Charles de Coster werd in 1827 in München geboren als kind van een Waalse vader en een Vlaamse moeder. Hoewel hij Franstalig was, koesterde hij een grote sympathie voor de cultuur en volkstaal van Vlaanderen. Het idee voor zijn roman ontstond tijdens zijn studies aan de Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), waar zijn vriend Félicien Rops in 1856 een satiristisch tijdschrift had opgericht: "Uylenspiegel. Journal des débats littéraires et politiques".

De Tijl Uilenspiegel van Charles de Coster is, zoals we al eerder zagen, een vrijheiddsstrijder: een Vlaamse Ivanhoe of Willem Tell, die aan de zijde van de Geuzen tegen de Spaanse overheersing vecht. De vermakelijke dialogen tussen de twee personages doen onmiskenbaar denken aan dat andere onsterfelijke meester-en-knecht-duo: Don Quichot en Sancho Panza.

De in die jaren bloeiende Vlaamse Beweging, die ijverde voor het heropleven van de Vlaamse cultuur, sloot deze strijdbare, flamingante Tijl in haar hart. Zo werd de De Costers roman, contradictorisch genoeg, een Franstalige hulde aan Vlaanderen...

Het liberalisme van Tijl Uilenspiegel:

De Tijl van Charles De Coster heeft een vrijzinnige, vrijgevochten levensvisie, net zoals zijn schepper, met een drang naar waarheid en eerlijkheid. En net zoals de schrijver zelf werd Tijl een sociaal-bewogen figuur, bezeten door een drang naar zelfbeschikking in een brede humanistische instelling.

Een onverbeterlijke papenvreter:

De antiklerikale elementen komen al in het begin van het boek aan bod als de pasgeboren Tijl maar liefst vijf keer gedoopt wordt op één dag.

Toch is Tijl op zich geen godsdiensthater. Wel uit hij scherpe kritiek op de godsdienstoorlogen (het boek speelt zich af tijdens de hoogtijdagen van de Contrareformatie) en de kettervervolgingen die het land teisteren. Zijn vader komt op de brandstapel, verdacht van Lutherse sympathieën, de min Kathelijne verliest haar verstand na de vreselijke folteringen die zij, beschuldigd van hekserij, moet doormaken. Uilenspiegel observeert en klaagt het onrecht en de misbruiken van de inquisitie aan: een vrijbuiter die, letterlijk, god noch gebod kent: zo verhuurt hij zich bij de pastoor en steelt diens paard, en verkoopt hij paardenmest aan Joden, hen wijsmakend dat het om profetische korrels gaat waarmee ze de wederkomst van de messias kunnen voorspellen. Gestraft en veroordeeld tot het maken van een bedevaart naar Rome neemt Tijl ook de paus zelf in het ootje!

"Tijl Uilenspiegel" later herwerkt en bewerkt:

Het boek van Charles de Coster is bewerkt door vele andere auteurs:

een van de bekendste bewerkingen is de theaterversie die Hugo Claus in 1965 van de Uilenspiegel-legende maakte.

Willy Vandersteen maakte twee stripalbums rond Tijl Uilenspiegel, maar voegde er echter een vleugje van zijn eigen fantasie aan toe. Er wordt ook in de stripreeks Suske en Wiske ook een paar keer naar Uilenspiegel verwezen. In De stalen bloempot (1950) wandelen Lambik en Wiske langs de haven van Amoras, wanneer Lambik de knappe verwezenlijkingen van Vlamingen in het verleden begint te roemen, waaronder ook Tijl Uilenspiegel. Wiske merkt echter op: "Als je maar niet vergeet dat Lamme Goedzak de makker van Tijl Uilenspiegel was mag je voortpraten, Lambik." In De Krimson-crisis (1988) wordt Tijl Uilenspiegel naar het heden geflitst.

Richard Strauss schreef het symfonisch gedicht (Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche), geïnspireerd op de legende.

In 1961 liep er een gelijknamige jeugdserie over Tijl Uilenspiegel.

blz: 580 blz., met twee zwart/wit illustraties