Enlarge image

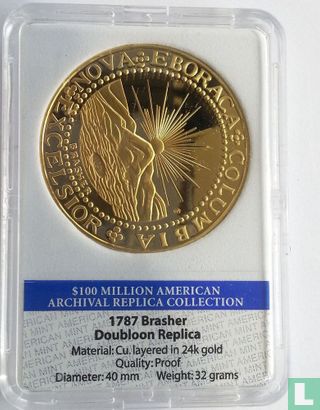

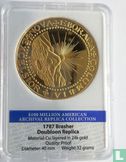

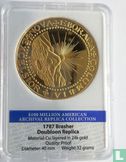

USA Brasher Doubloon (breast replica) 1787

Catalogue information

LastDodo number

5611503

Area

Tokens / Medals

Title

USA Brasher Doubloon (breast replica) 1787

Publisher

Value

Country

Year

2013

Collection / set

Material

Weight

Variety / overstrike

Obverse

UNUM * E * PLURIBUS 1787 (EB)

Reverse

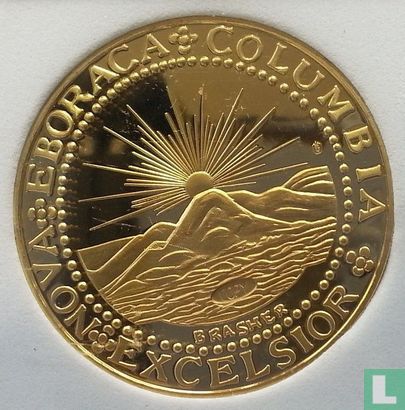

NOVA * EBORACA * COLUMBIA * EXCELSIOR brasher (copy)

Privy mark

Mint mark

Designer

Engraver

Dimensions / Diameter

40 mm

Number

Details

1787 New York Brasher Doubloon,

- The Numismatic "Holy Grail" !!

It is the only Pre-Federal American Gold Coin (W-5840), and is among the great rarities of American numismatics. The 1787 New York Brasher doubloon is in a class of its own, and has been acknowledged as the most important and valuable coin in the world by such luminaries as Henry Chapman and Q. David Bowers. When Fort Worth coin dealer B. Max Mehl offered the present coin in his James Ten Eyck catalog in 1922 he noted, "For historical interest and numismatic rarity, this great coin is second to none. It is rightfully recognized as one of the greatest numismatic rarities of the world." Heritage Auctions is privileged to offer the finest-certified example of this iconic numismatic treasure in the January 2014 FUN sale.

The Brasher doubloon has been called the most valuable coin in the world on many occasions, and its record of prices realized at auction and private sale does much to confirm this claim. The rare coin market rises and falls over time, and some other rare issues that are offered more frequently have occasionally eclipsed the prices realized by the Brasher doubloon in its rare auction appearances, but in head-to-head competition, the Brasher always comes out on top. When Henry Chapman sold the fabled collection of Mathew Adams Stickney in 1907, the Stickney doubloon far outdistanced one of the finest and most famous examples of the 1804 dollar offered in that same sale, realizing $6,200 (a world record for any coin at the time) to $3,600 for the dollar. The coin offered here also easily bested the 1804 dollar in the Ten Eyck sale. Even the redoubtable 1822 half eagle and the unique 1870-S three dollar gold piece in the Eliasberg Collection had to settle for a second-place tie behind the Stickney-Garrett specimen of the Brasher doubloon when those great collections were sold in close proximity in the late 1970s-early 1980s. The recent private sale of the AU50 Bushnell Brasher doubloon for nearly $7.4 million suggests that this finest-certified MS63 example is poised to reclaim its title of "World's Most Valuable Coin."

To understand the importance of the Brasher doubloon it is necessary to know something about its creator, a multi-faceted man named Ephraim Brasher. Brasher was a man of many accomplishments and fairly well known in his time, but history had largely forgotten him until scholars began researching his life in conjunction with his numismatic legacy. Much has been learned about Brasher and his coins in recent years, but some questions remain unanswered.

Ephraim Brasher, Silversmith, Patriot, Businessman was born April 18, 1744 to an old Dutch family in New York.

Different branches of the family spelled their name variously as Breser, Bresert, Brasier, Brazier, and even Bradejor.

Brasher enlisted in Colonel Lasher's regiment of the New York Provincial Army as a Lieutenant of grenadiers in 1775 and may have served in the battles of Brooklyn and Manhattan Island. He definitely served on the New York Evacuation Committee in 1783, supervising the handover of the city from the British occupying forces. He rose to the rank of major in the militia after the war, retiring in 1796.

One of Brasher's chief claims to fame was that he lived just a few feet from President George Washington in New York City after the war. Washington resided at 3 Cherry Street and Brasher lived next door at 1 Cherry Street. Some sources give Brasher's address as 5 Cherry Street. Cherry Hill was a fashionable section of New York in the 18th century, located just north of the Manhattan side of the present day Brooklyn Bridge. Brasher's business address was 77 Queen Street, not too far north of his home. Not only were Washington and Brasher neighbors, but Washington was also a customer of Brasher. He owned numerous silver pieces made by Brasher, including a number of silver skewers with a surviving receipt. It was certainly important for Washington to make a good impression at state dinners, which he did with the assistance of his Brasher silver.

Brasher was a well-respected member of the community. In his March 1987 Coinage article, "The Brasher Bicentennial," David T. Alexander noted: "In the late 1700's, silversmiths and goldsmiths were particularly respected members of the community, often acting as bankers, assayers, and authenticators of the Babel of gold and silver coins of the world which circulated in the bullion-starved colonies and the new republic." Later, he served in local politics in New York, almost like serving in national posts at the time. New York was the leading center of banking and foreign trade, and was also the new national capital. He served as sanitary commissioner from 1784 to 1785, coroner from 1786 to 1791, assistant justice from 1794 to 1797, election inspector from 1796 to 1809, and commissioner of excise from 1806 to 1810. The Old Middle Dutch Church records say he died on November 10, 1810, aged 66.

Brasher the Assayer

---------------------------

According to Walter Breen, an entry in the July 1892 edition of the American Journal of Numismatics reveals that Brasher was employed, along with David Ott, to assay a number of foreign gold coins received by the newly founded United States Mint in 1792. This is confirmed by an entry in the American State Papers under "Estimated Expenditures for the Year 1796" in which a $27 Treasury Warrant was recorded:

"... in favor of John Shield, assignee of Ephraim Brasher, being for assays made by said Brasher, in the year 1792, for the Mint of sundry coins of gold and silver, pursuant to the instructions from the then Secretary of the Treasury."

The assay of foreign coins was a yearly requirement for the Mint and the results were reported for many years in the annual Report of the Director of the Mint. Unfortunately, the assays could not be legally conducted at the Mint in 1792 because Chief Assayer Albion Cox was unable to pay the $10,000 bond required by Congress to perform precious metal coinage operations. This situation persisted until 1794, when Congress lowered the requirement and Cox was able to provide the surety, with the help of Mint Director David Rittenhouse. Until that date, the assay had to be outsourced, and Brasher, Washington's old neighbor, was a natural choice for the job.

The necessity for these assays was widespread in the later part of the 18th century, when the money supply in the fledgling United States consisted of a bewildering hodge-podge of foreign coins, private issues, and state sponsored copper coinage, all mixed with counterfeits and coins of reduced weight that had their edges clipped or were "sweated" with acid. Gold coins were primarily used in large transactions by banks or merchants in the larger cities and most people never handled them. Most of the gold coins in circulation were from Portugal, Great Britain, France, Spain, and the many mints in Spanish colonies in the New World. In 1789, the Bank of North America advertised the values of various foreign gold coins and tables were published by other institutions to help merchants conduct the everyday business of commerce. Before the Mint was established, private individuals and banking institutions carried out assays on circulating coins and, although there is some doubt about this, it is believed that Brasher performed this service for many of his customers.

A number of foreign gold and silver coins are known today that bear Brasher's trademark counterstamp (see Figure 2). It is thought that Brasher evaluated these coins and stamped them to signify that they were of full weight and fineness. The Bank of New York employed gold and silversmiths, like Brasher, to test the coins that came into the bank. These men were known as "Regulators" and they would weigh each coin as it was deposited and add a plug of gold to any that were found to be outside the allowable tolerances, stamping the coin with their stamp to indicate that the coin was of proper weight and consistency. These coins are highly regarded and sought-after by collectors today. Brasher's reputation as an assayer was apparently well-established by the late 1780s, and his counterstamp was widely accepted as a guaranty of value.

Brasher's Private Coinage

Brasher's skill as a silversmith, engraver, assayer, and metal worker enabled him to branch out into the field of private coinage for which he will always be remembered. His first endeavor in the field seems to have been the Lima Style doubloon, which resembled the widely circulated 1742-dated Spanish coins of the 8 Escudos denomination. The 8 Escudos coins were called Doblons in the Spanish colonies and the term was adopted and Anglicized to doubloon in the United States. They were worth $16, a large sum for the average man in the late 1700s.

The Lima Style doubloon is a mysterious coin, about which little is known today. It was probably the first of Brasher's personal coin issues to exhibit his distinctive counterstamp and several theories have been advanced to explain its production. Walter Breen believed the Lima coins were produced after the better known New York Style pieces, but Michael Hodder demonstrated that they actually predate their New York counterparts. In his article in the Coinage of the Americas Conference series titled "Ephraim Brasher's 1786 Lima Style Doubloon," Hodder showed that the EB punch used on the Lima doubloons was in an earlier die state than it was in its later use on the New York doubloons, where it showed signs of die rust above the upright of E, inside the top space of E, above and right of the crossbar, and over the inside right curve of B. The Lima Style doubloons were probably minted in 1786 and the mintage is unknown, but it must have been small. Only two examples of the issue survive today. Some researchers have suggested that they were struck as patterns. Others believe that they were struck as circulating gold issues for use in the lucrative West Indies trade. They may have been the first American trade coins, serving the same role as the Trade dollars of the 1870s did in the China trade. Whatever their purpose, they were closely related to Brasher's more famous New York issue, as the weight and fineness of the two issues are virtually identical.

Brasher next tried his hand at copper coinage. An article by Louis Jordan on the Notre Dame website states:

"In 1787 Brasher appears to have joined with the New York silversmith and noted sword maker, John Bailey in requesting a franchise to produce copper coins for the State of New York. The legislative record for February 12, 1787 stated, 'the several petitions' of Brasher and Bailey were filed with the state. Because of the ambiguous wording it is not known if the petitions were joint ventures or simply individual petitions that just happened to have been submitted on the same day."

As Jordan points out, it is possible that the two men were operating independently, but it is much more likely that they acted together. Unfortunately, the committee considering the matter decided that their mandate did not extend to authorizing a state coinage and opted instead to formulate a bill to regulate the coinage that was already in circulation. No contract was awarded to Brasher and Bailey, or to Thomas Machin, who submitted his own petition at about the same time.

Despite this setback, Brasher and Bailey proceeded to strike copper coins on their own, using a design that resembled the Connecticut state coppers of that era. The blanks were obtained from Colonel Eli Leavenworth of New Haven, Connecticut and the design featured an armored male bust on the obverse and a seated figure of Liberty on the reverse. The number punches and the four-lobed rosettes (quatrefoils) that were used on these pieces, known as Nova Eborac coppers, were later employed to prepare the dies for Brasher's famous doubloon. Their resemblance to the familiar Connecticut pieces and their semi-official appearance undoubtedly aided in the wide acceptance of the Nova Eborac coins.

The New York Style Doubloons

Brasher created his numismatic masterpiece, the New York Style Brasher doubloon, sometime in 1787. Although the specifications for the coin are virtually identical to the Lima doubloons and are extremely close to those of the earlier Spanish coins that served as their prototype, the design was something altogether new:

Obverse: The obverse was apparently adopted from the state coat of arms of New York. The sun is rising over the peak of a mountain with a body of water in the foreground. Brasher's name is spelled out below the waves, in small letters. This central device is enclosed within a circle of beads. The legend, around: NOVA EBORACA COLUMBIA EXCELSIOR has each word separated by a rosette. The legend translates to New York, America, Ever Higher. Excelsior remains the state motto to this day.

Reverse: An eagle with wings displayed, and a shield covering its breast, has a bundle of arrows in its sinister claw (to the observer's right) and an olive branch in its dexter claw. Thirteen stars surround the eagle's head. This central device is enclosed in a continuous wreath. Around, the legend: UNUM E PLURIBUS with the words separated by stars. This legend translates to One of Many. Below, the date 1787 is flanked by rosettes. Many of these devices are similarly used on the Great Seal of the United States. Like many coins of this era, the denomination was not specifically expressed anywhere on the coin.

On one example of the New York Style doubloon Brasher impressed his counter stamp on the shield on the eagle's breast. On the other six known specimens, the counter stamp was placed at slightly varying locations on the eagle's left (facing) wing. The specifications for the issue were:

Weight: 26.66 grams (per Walter Breen).

Diameter: 28.6 mm (per Walter Breen).

Die Alignment: 180 degrees, or coin-turn alignment.

Edge: Plain.

Composition: gold approximately 89%, silver approximately 6%, copper approximately 3%, trace elements 2%.

The composition is interesting, as it varies from the earlier Spanish doubloons, which were approximately 90% gold, 8% silver, and 2% copper. Later U.S. gold coins reversed this ratio of silver to copper, keeping the gold at 90%. This shows that Brasher must have assayed his gold and refined it himself to meet his unique standard of fineness, rather than just melting a cache of older Latin American gold pieces to use in striking his doubloons. The different alloy for the later federal gold coinage proves that the doubloons were not fantasy pieces, struck at a later date from melted down U.S. coinage. At least one example of a half doubloon exists, now in the National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution. It was struck from the same dies as the regular doubloons on an undersized planchet weighing half as much as the larger coins.